Architecture:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Goodrich House

Frank Lloyd Wright designed the Goodrich House in 1896, three years after he launched his independent architectural practice. The house’s design was based on a series of plans that Wright had developed for his Oak Park client, Charles E. Roberts. Still quite early in his career, Wright experimented with ideas that would influence his emerging Prairie style.

Side Elevation for House for Mr. C. E. Roberts, house number 2. January, 1896. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Architect (The Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York).

Widely recognized as one of the greatest architects in American history, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) designed more than 1,000 buildings, and his work and ideas continue to garner attention across the globe today. Wright designed the Goodrich House in 1896. He was in his late twenties, and this was an early and important period in his career.

After working under renowned Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, Wright launched his own independent practice in 1893. At that time, he and his wife Catherine had a growing family, and the young architect needed to establish himself quickly. Wright built a home for his own family in Oak Park, Illinois, onto which he soon added a studio for his practice.

Charles E. Roberts in an electric car that he built for himself, ca. 1897, Oak Park River Forest Historical Society.

Self Portrait Photograph of Frank Lloyd Wright, ca. 1905. Collection of Frank Lloyd Wright Trust.

During the early 1890s, the nation was in a recession, and there was plenty of competition among Chicago’s many architecture firms. Through his Oak Park neighbors, friends, and fellow Unitarians, Wright secured numerous commissions in the area. One of his most important acquaintances was Charles E. Roberts (1843-1943), a successful inventor, mechanic, and businessman. Roberts was a prominent community leader who became a key mentor to the young architect.

Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio, Oak Park, Illinois. Allix Rogers, Photographer.

In 1896, Roberts commissioned Wright to design several projects, including remodeling and enlarging his own home at 321 N. Euclid Avenue and designing a summer house for the family. In an even more ambitious project, Roberts had Wright design a speculative development for a block of approximately eighteen homes for middle-class residents in the Ridgeland area of Oak Park.

During this period, many of Wright’s clients were quite affluent. Projects like the Winslow House (River Forest, 1893) and the Moore House (Oak Park, 1895) show his creative approach for clients with large lots and generous budgets.

While Roberts’ proposal called for relatively modest houses on smaller lots, this project offered Wright an exciting opportunity. It enabled the young architect to explore ideas about how to design affordable, high-quality residences that would maximize privacy while also promoting a sense of community.

Winslow House, River Forest, 2024.

Nathan G. Moore, Residence, Inland Architect, Volume 31, 1898.

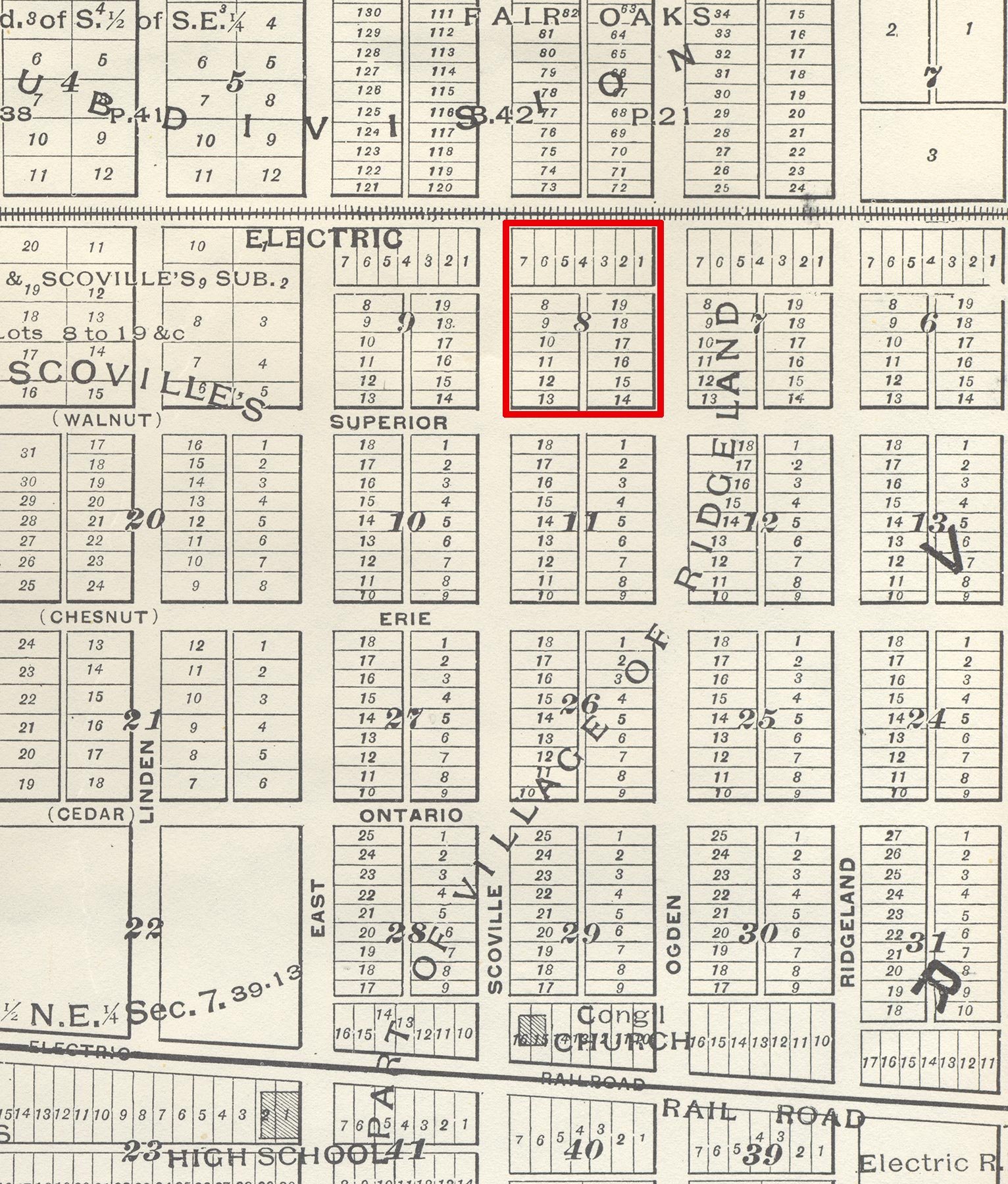

Roberts acquired a full block between Chicago Avenue and Superior Street and Ogden (now Elmwood) and Scoville Avenues between 1889 and 1895. According to Neil Levine, author of The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright, this part of Ridgeland had been platted into evenly-arranged lots more than a decade earlier. By the time Wright and Roberts started their plans, the unimproved block had no houses, sidewalks, or even streetlights, so they were not restricted by the earlier subdivision map.

1894 Map of the Ridgeland section of Oak Park, highlighting the block purchased by Charles E. Roberts for his proposed development. Part of a map distributed by real estate salesmen Kennedy & Ballard. Courtesy of Oak Park River Forest History Museum.

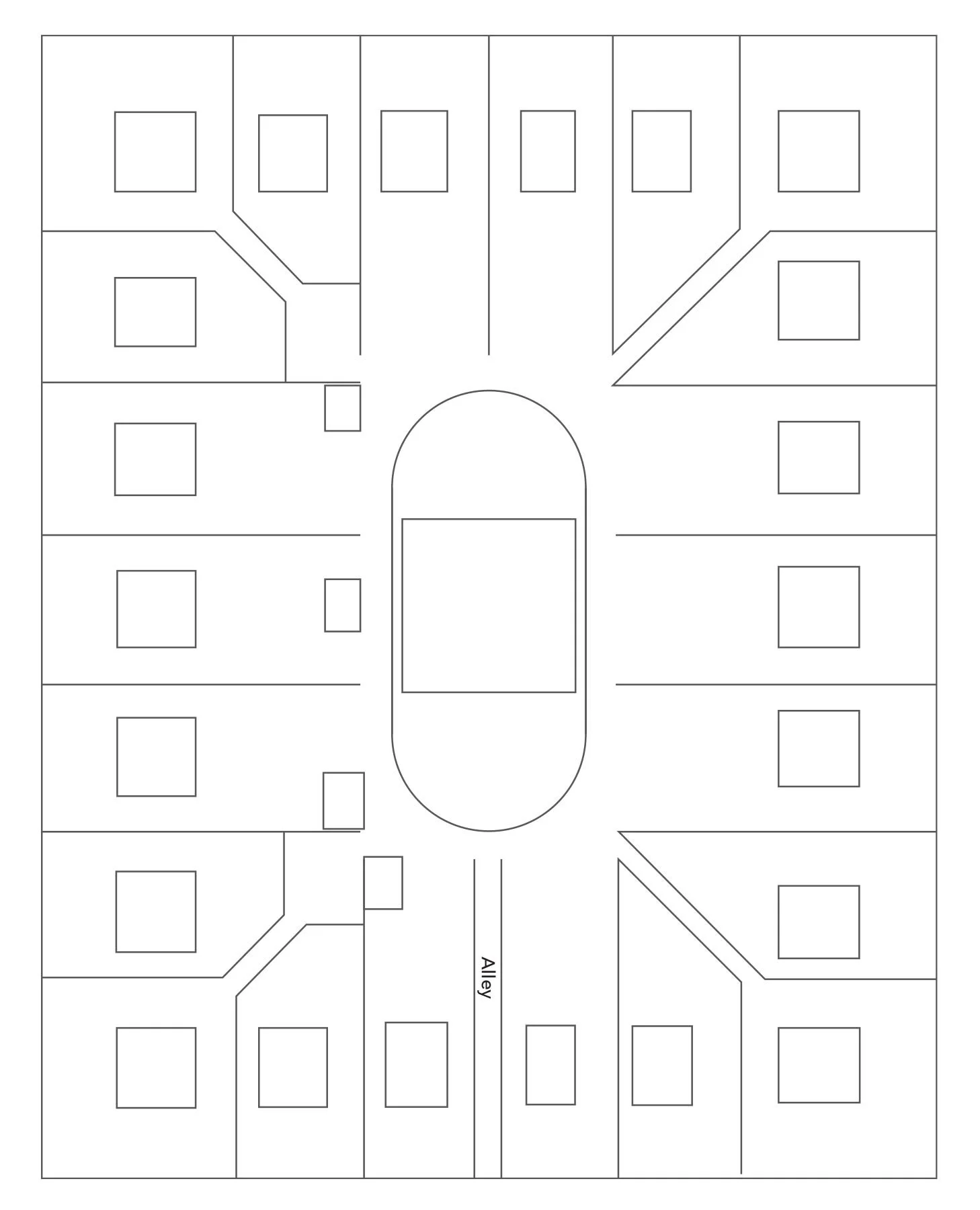

Wright created an initial study for the block on graph paper. Noting that graph paper was not commonly used by American architects of the period, Levine explains this plan represents “Wright’s earliest known use of gridded paper.” In faint pencil, the plan shows house footprints, passageways, and an unidentified central space.

Contemporary schematic representation of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Block plan for Charles E. Roberts, 1897, showing the proposed layout of houses around the edge of the block with a central area of unidentified purpose.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Block Plan for Charles E. Roberts, 1897. Done on graph paper, an unusual medium for architects at this time. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Wright completed a set of over fifty drawings of six different model houses for the Roberts development. The proposed homes were each two stories tall and approximately 2,200 square feet in size. These residences were largely traditional in appearance but with unusual details, some of which hinted at Wright’s evolving Prairie style.

“Rather than serving as an abstract compositional tool to control the design and ultimately the construction of an individual building, the grid here materially defines the terrain of a community of houses. It echoes the preexisting grid that governed the platting of the suburb itself and thus makes it clear that Wright conceived the Roberts project in terms of the larger physical and cultural network of Chicago.”

Neil Levine, The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright

Although the Roberts development never materialized, it seems that Wright used some of the plans as presentation drawings for new clients, including Harry and Louisa Goodrich. How the Goodriches first met Frank Lloyd Wright is unknown, but it seems likely that Charles E. Roberts made the introduction. He and Harry Goodrich were both inventors and the two had worked closely together as directors of the Chicago Screw Company roughly two decades earlier.

By the mid-1890s, Harry and Louisa Goodrich’s children were adults, and most had married and moved out of the family’s spacious home on West Washington Boulevard in Chicago. The couple may have had some financial challenges at the time, and thus downsizing and moving to the quaint suburb of Oak Park likely provided a practical solution.

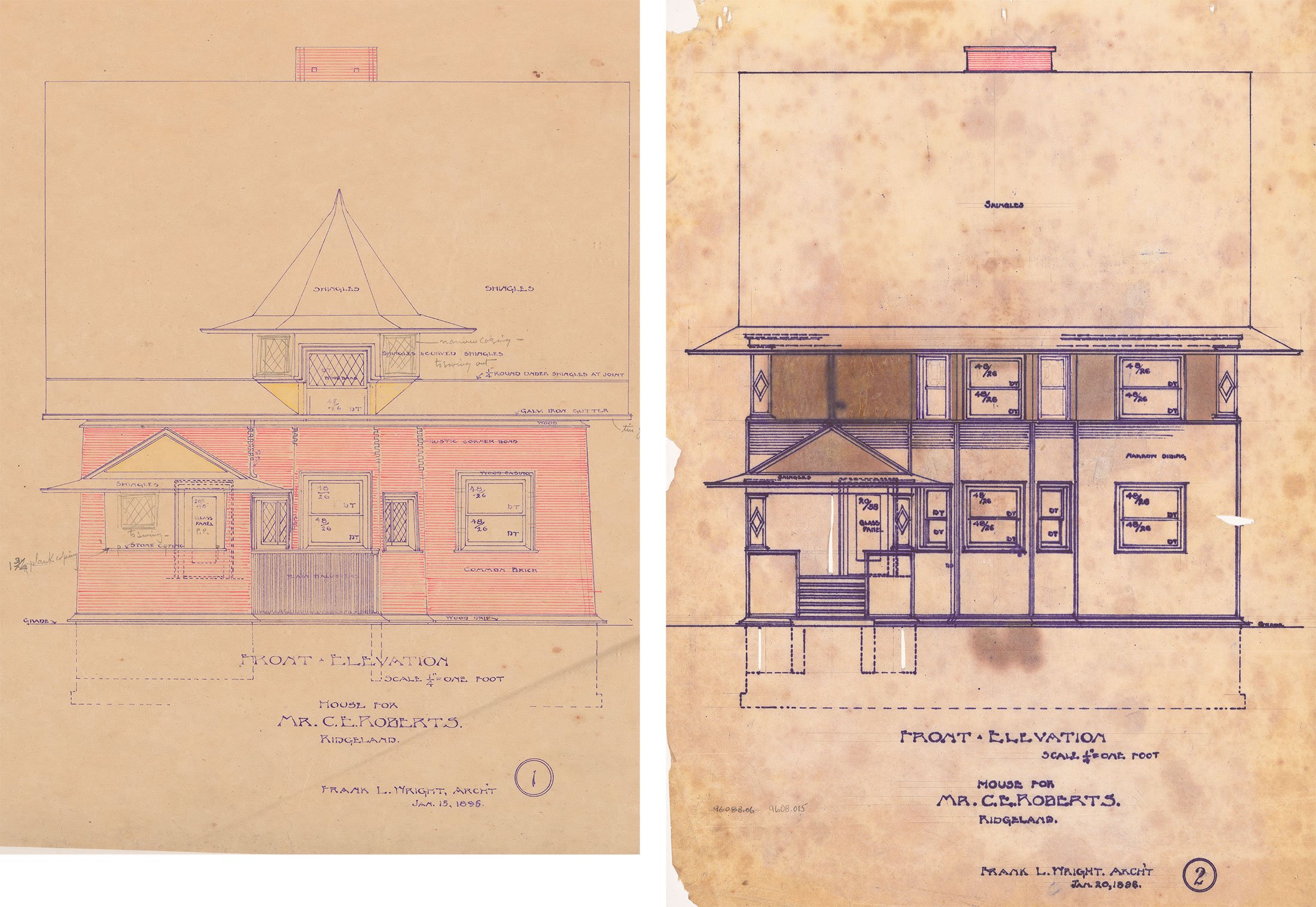

As he started working with the Goodriches, Wright seems to have combined features of the Roberts model house labelled number 2 with some aspects of house number 1. Wright had prepared these two set of plans in January 1896.

By mid-June of that year, Louisa Goodrich had purchased a lot on North East Avenue to build the home. Louisa would hold the mortgage once the house was built. On September 4, 1896, the Oak Park Reporter announced that the Goodrich House was under construction following plans by Wright.

Chicago Screw Company advertisement showing H. C. Goodrich as President and C. E. Roberts as Secretary, Scientific American, January 22, 1876, p. 60.

The Goodrich house design largely followed house number 2 (right image), with the porch entrance turned as in house number 1 (left image).

Model houses for Mr. C. E. Roberts in the Ridgeland project, January, 1896. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Architect (The Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York).

Oak Park Reporter, September 4, 1896, page 4.

Wright’s perspective drawing for house No. 2. January 1896. It is unclear when Wright added the hipped roof revision (shown in pencil). However, the Goodrich house retained the gable roof shown in the original drawing.

The Goodrich House in 2025, shown in a similar view to Wright’s perspective drawing for house No. 2.

Photograph published in 1900 of Goodrich House from Architectural Review (June 1900).

The Goodrich House in 2025, shown in a similar view to the 1900 photograph.

The Goodrich House exterior features a steeply-pitched gable roof that flares out at the base to form dramatically deep eaves. Clapboard siding stretches across the first story and rests on a heavy, flared skirt board which merges the house silhouette with the surrounding ground. With a design feature that allowed Wright to subtly emphasize horizontality, stucco on the second story changes the wall texture. A continuous band of molding between the clapboard and the stucco enabled Wright to accommodate the slight setback between the two stories.

Front and rear porches are capped by distinctive roofs that repeat the flared eaves. These porches, which project into the surrounding landscape, were a departure from the shallow, wrap-around porches more typical of the Victorian era. Based on Wright’s model house 1, the Goodrich House stairs are approached from the side rather than head on. These stairs are concealed by a screen of tall balusters with a heavy top rail and newel posts with large globe-shaped finials. This treatment hints at the preferred “hidden” entrance and private outdoor living space that were becoming Wright signatures.

View of second-story windows, 2025. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Most of the Goodrich House’s windows are simple: square in dimension and double hung with large, undivided panes. However, the second story windows within the three-sided bay are distinctive. These casement windows have lively decorative muntins. On the north elevation, a tall window with a matching decorative motif lights the stair hall. Wright’s theme for the house—diamonds and lozenges—was expressed in these windows and on the exterior columns and pilasters.

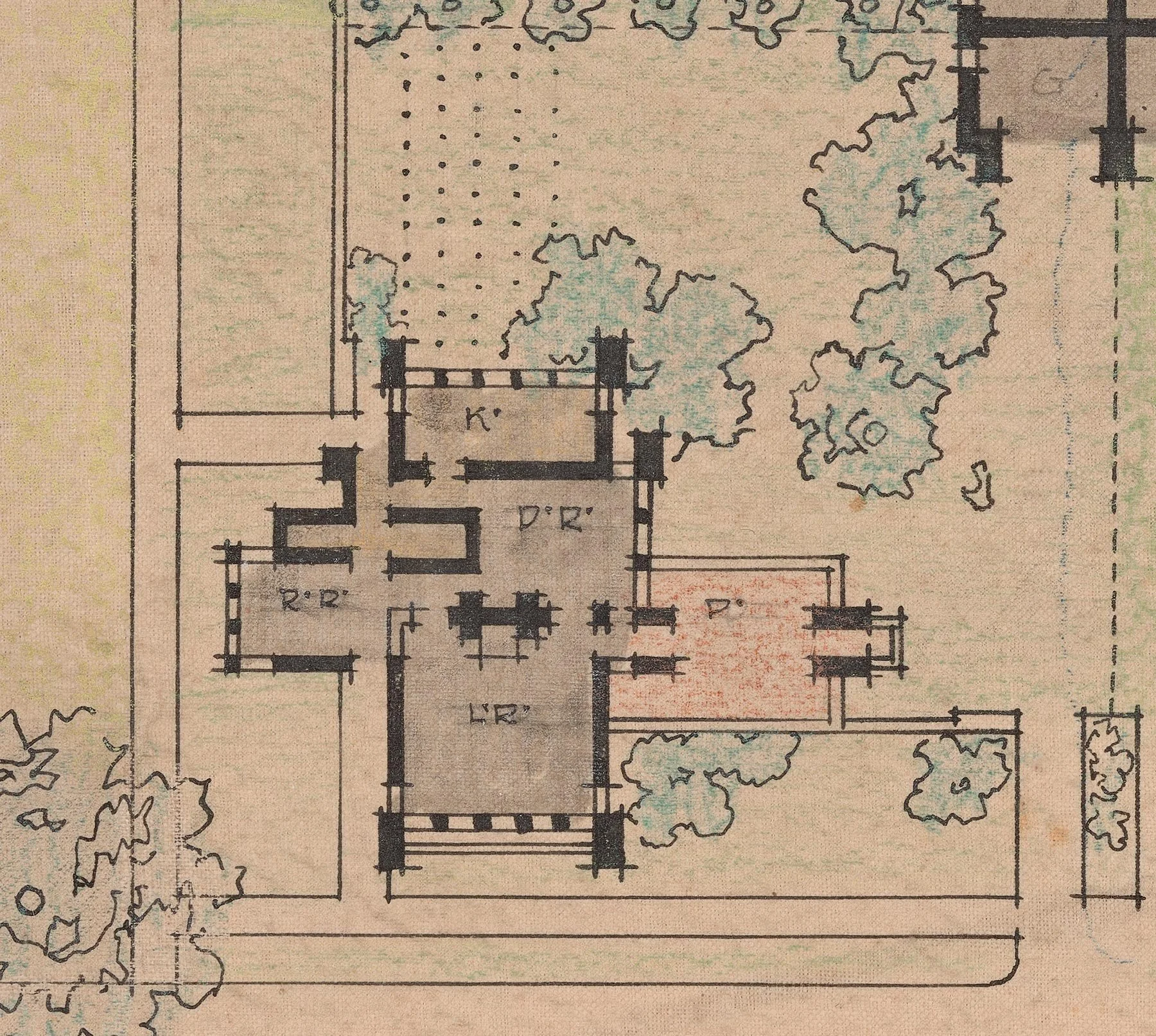

Grappling with new ideas about how to design a comfortable middle-class suburban home, Wright created an open floor plan that he used many times in the 1890s, including in his own home.

At the Goodrich House, this featured a large entry hall and spaces that flowed easily from one room to the other. The comfortable sitting room had a deep, three-sided bay across from a cozy fireplace inglenook. As was typical of this plan, Wright tucked the pantry and kitchen in the rear corner.

This close-up view shows the dramatic overhang and strong sense of horizontality articulated by the band beneath the roofline. 2025 Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Frank L. Wright’s Floor Plan for House for Mr. C. E. Roberts, House No. 2, January, 1896.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Architect (The Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York).

Close up view of porch column with decorative diamond element, 2025. Photo by Julia Bachrach.

Modest residences like the Goodrich House inspired Wright to publish “A Small House with ‘Lots of Room in It’,” in the Ladies Home Journal in 1901. In this article, Wright focused on making a house “comfortable with modest outlay.” Suggesting that the “average home-maker is partial to the gable roof,” he recommended a feature that can be seen in his design for the Goodrich house: “gently flaring eaves… slightly lifted at the peaks.”

Wright remained fascinated with the topic of designing a neighborhood of affordable homes. Roberts wanted to move forward on his speculative development, and he had Wright prepare new plans for the project in 1903. As Neil Levine explains in an article entitled “Wright’s Geometry of Community,” revisiting the project gave Wright the opportunity to explore new ideas about community planning. Levine explains that in his “initial project for the Roberts block” Wright laid the houses out following the “standard system of lining up individual houses along the four street fronts while leaving an area in the center of the block for a garden.” In his 1903 drawings, often referred to as the Quadruple Block Plan, Wright grouped the houses into units of four and oriented them “as much, if not more, to each other than to the street.” Levine points out that in this arrangement “the communal space around and between [the houses] is not a leftover but a result of their geometric interaction.” Wright continued to experiment with this idea in later plans.

Cover of “A Small House with “Lots of Room in It,” Ladies Home Journal, July, 1901.

Wright’s Development Plan for Charles E. Roberts, Unbuilt Project Block Plan, 1903. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York).

Detail showing labeled rooms in the Unbuilt Project Block Plan, 1903. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library Columbia University, New York).

“The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright,” by Robert C. Spencer Jr., Architectural Review, June 1900, p. 63. Described as a cottage for Mr. Goodrich, the Harry and Louisa Goodrich House is shown in the upper left corner of the page. This is the first published article that includes a photograph of the Goodrich House.

Unity Temple. Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archive, ca. 1908.

A 1975 article in the Oak Park River Forest World newspaper explains that Charles E. Roberts was pivotal in making Unity Temple happen. According to Marion Herzog (the granddaughter of a church leader who had voted against the Wright design), when her grandfather became skeptical about the project, Roberts had Wright create a model and the two men “explained the building to the committee.” After this presentation, the board voted in favor of building Wright’s radical plans for Unity Temple. The building is recognized as one of his most important works—it is listed today as a National Historic Landmark and as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Visitors who flock to Oak Park to see Unity Temple and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio may not be aware that Wright was deeply devoted to improving the design of moderately-priced homes like the Goodrich House. However, a 1900 article in Architectural Review by Wright’s friend and colleague, Robert Spencer, highlights this point.

Spencer published a photograph of the “Goodrich Cottage” alongside drawings and photos of more lavish projects like the Winslow House. Spencer wrote:

“Few architects have given us more poetic translations of material into structure than Frank Lloyd Wright… That some of this work has been the designing of simple houses of the less costly sort, does not detract from, but rather adds to the interest which it should inspire.”

The Goodrich House is a fascinating example not only of the early years of Wright’s Oak Park practice, but also his desire to create a pleasant, livable space for a middle-class family. As he had intended, the house continues to provide a comfortable home for an Oak Park family.

Charles E. Roberts never built any of his proposed housing developments. In fact, he sold the unbuilt land in 1906. Nevertheless, Roberts played an instrumental role in Wright’s career. As a member of the board of trustees for Unity Temple, he helped Wright secure the commission to design the revolutionary Oak Park church in 1906.